History of Israel

Discover the rich heritage, ancient connections, and modern achievements of the Jewish people and the State of Israel

Construction of Dome of the Rock , Al Haram Al Sharif

The Dome of the Rock and the Jewish Foundation Stone: History, Theology, and the Enduring Bond Between Israel and Jerusalem

Few locations in the world carry the historical depth and spiritual gravity of Jerusalem’s Temple Mount. For Judaism, this site—known as Har HaBayit—is the holiest place on earth. Long before the construction of the Dome of the Rock, the Temple Mount was the location of the First Temple built by King Solomon and the Second Temple, the center of Jewish worship for nearly a thousand years.

At the heart of this sacred precinct lies the Foundation Stone, the Even ha‑Shetiyyah, a cornerstone of Jewish theology. Today, the Islamic shrine known as the Dome of the Rock stands above it, built in the late seventh century CE. Understanding the Jewish significance of this site is essential to understanding both Jewish history and the modern connection of the Jewish people to Jerusalem and the State of Israel.

The Foundation Stone in Jewish Tradition

Jewish tradition identifies the Foundation Stone as the spiritual and physical center of creation. Classical sources describe it as the point from which the world was formed and the place where the waters of the deep were restrained. According to the Mishnah and Midrash, the stone lay beneath the Holy of Holies, the most sacred chamber of the Temple, where the Ark of the Covenant once rested.

The Foundation Stone is also associated with the Binding of Isaac, a central narrative in Jewish tradition. Later Jewish writings consistently identify this location as the site where Abraham prepared to offer Isaac, further elevating its sanctity.

This stone is therefore not merely a geological feature but a theological axis, the meeting point of heaven and earth, and the center of Jewish cosmology.

The Jewish Temples on the Mount

The First Temple (c. 957–586 BCE)

Built by King Solomon, the First Temple was constructed around the Foundation Stone. It served as the central place of worship, sacrifice, and pilgrimage for the people of Israel.

The Second Temple (516 BCE–70 CE)

Rebuilt after the Babylonian exile, the Second Temple stood for nearly six centuries. Herod the Great expanded the Temple Mount into the massive platform visible today. For generations, Jews ascended to Jerusalem three times a year, and the Temple served as the heart of Jewish religious life.

For more than a millennium before the Dome of the Rock existed, the Temple Mount was the undisputed spiritual center of Judaism.

The Dome of the Rock: Historical Context and Construction

The Dome of the Rock is an Islamic shrine, not a mosque. It was constructed long after the destruction of the Second Temple.

According to historical sources:

Construction began around 685 CE under the Umayyad caliph Abd al‑Malik ibn Marwān.

It was completed between 691 and 692 CE.

It is the oldest surviving Islamic monument and was built around the rock that Jews identify as the Foundation Stone.

Islamic tradition later associated the rock with Muhammad’s ascent to heaven, but this association developed centuries after Jewish tradition had already sanctified the site.

Jewish Significance Beneath the Dome

The Dome of the Rock was intentionally built over the Foundation Stone, the holiest point in Judaism. Jewish sources identify this stone as:

The site of the Holy of Holies.

The location of the Ark of the Covenant.

The place where the High Priest entered once a year on Yom Kippur.

The point from which creation began.

The stone that held back the waters of the deep, according to Midrashic accounts.

Even Islamic sources acknowledge that the structure was built on the site of the earlier Jewish Temple, known in Arabic as Bayt al‑Maqdis.

Historical Evidence of the Jewish Priority on the Site

Archaeological and textual evidence

Herodian stones, ritual baths, and Second Temple–period artifacts surrounding the Temple Mount confirm the Jewish presence and construction centuries before Islam.

Roman and Byzantine records

After the destruction of the Temple in 70 CE, Roman and Christian sources consistently refer to the site as the former location of the Jewish Temple.

Islamic writings

Early Islamic texts acknowledge that the Dome of the Rock was built on the site of the Jewish Temple, further confirming the Jewish identification of the location.

Jewish liturgy and continuity

For two thousand years, Jews prayed daily toward the Temple Mount, reciting prayers for the rebuilding of the Temple. This uninterrupted tradition is itself a historical witness to the centrality of the site in Jewish life.

The Modern Jewish and Israeli Connection

For the State of Israel and the Jewish people worldwide, the Temple Mount remains the holiest site in Judaism. It symbolizes Jewish continuity, identity, and the unbroken connection to Jerusalem.

Since 1967, Israel has ensured access to Jerusalem’s holy sites for all faiths, a level of religious freedom not consistently maintained under previous rulers.

Conclusion

The Dome of the Rock is an important Islamic shrine, but its location atop the Foundation Stone reflects a much older Jewish sanctity. For more than three millennia, the Temple Mount has been the spiritual center of Judaism, the site of the ancient Temples, and the focal point of Jewish prayer and longing.

Understanding the Jewish perspective on the Foundation Stone and the Temple Mount is essential to understanding Jewish history, identity, and the enduring bond between the Jewish people and Jerusalem.

( See Article : https://timetostandupforisrael.com/article/h History of the Dome Of The Rock, al Haram Al Sharif , in the history section / articles)

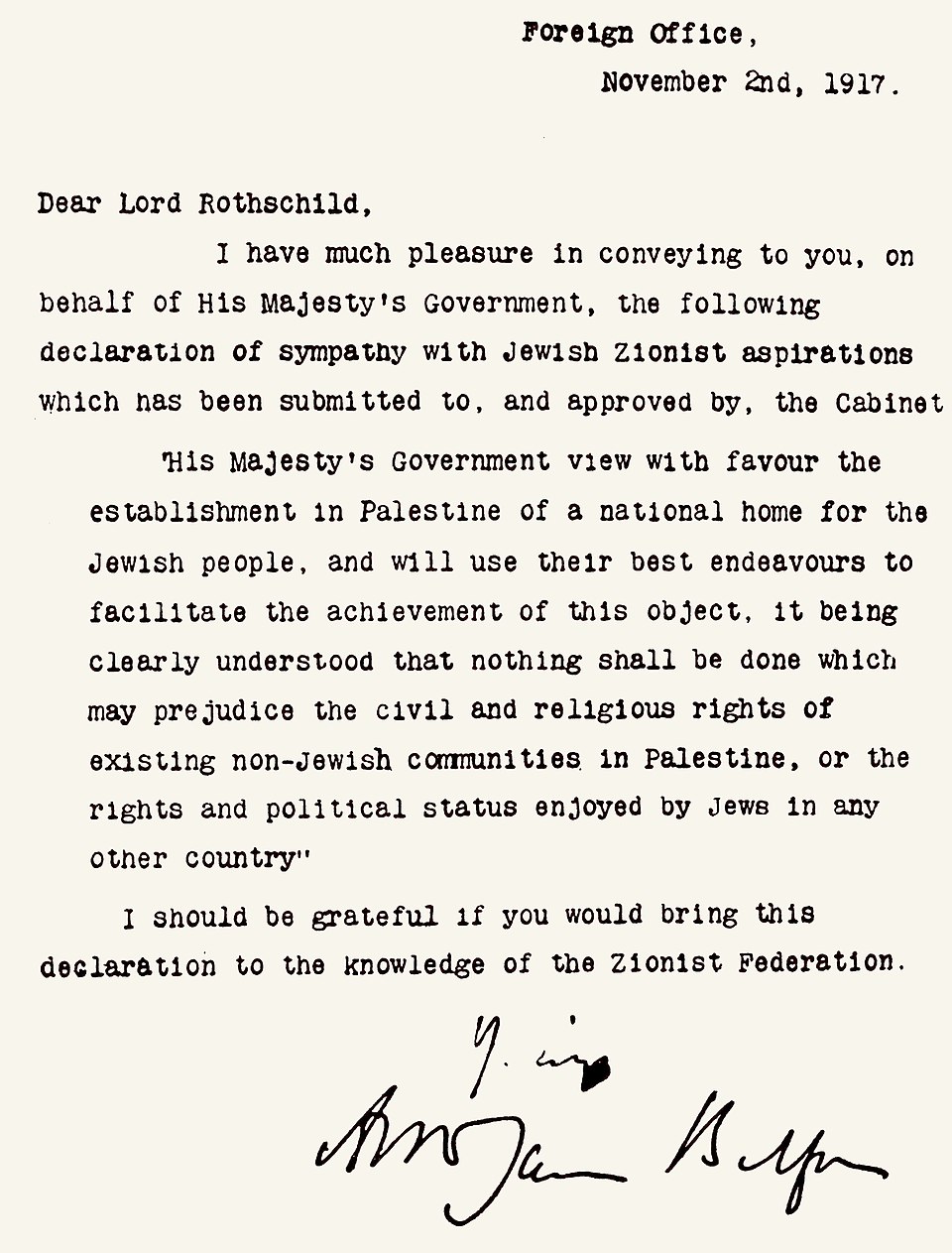

The Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British Government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman region with a small minority Jewish population. The declaration was contained in a letter dated 2 November 1917 from Arthur Balfour, the British foreign secretary, to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jewish community, for transmission to the Zionist Federation of Great Britain and Ireland. The text of the declaration was published in the press on 9 November 1917.

The harness the Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers for hydroelectric power.

Pinhas Rutenberg, a Jewish engineer who, in 1919, presented a detailed plan to harness the Jordan and Yarmouk Rivers for hydroelectric power. This was revolutionary thinking in a region still dependent on kerosene lamps and animal labor.

San Remo Conference

Conference of San Remo, (April 19–26, 1920), international meeting convened at San Remo, on the Italian Riviera, to decide the future of the former territories of the Ottoman Turkish Empire, one of the defeated Central Powers in World War I; it was attended by the prime ministers of Great Britain, France, and Italy, and representatives of Japan, Greece, and Belgium.

The Nebi Musa Riots

The Nebi Musa Riots: April 1920

During a religious festival in Jerusalem:

Jewish homes and synagogues were attacked

Jews were beaten, raped, and murdered

British forces largely stood aside

The Jews were unarmed civilians.

The British later admitted their failure, but the message to Jews was unmistakable:

They could rely on no one but themselves.

This realization directly led to the formation of Jewish self-defense organizations, not aggression, but survival

The Peel Commission

Peel Commission, group headed by Lord Robert Peel, appointed in 1936 by the British government to investigate the causes of unrest among Palestinian Arabs and Jews. In July 1937 the commission recommended the mandate be partitioned into an Arab state and a Jewish state, but the idea was ultimately rejected in 1938 as infeasible. The commission’s findings influenced UN Resolution 181 (1947), which likewise called for partition.

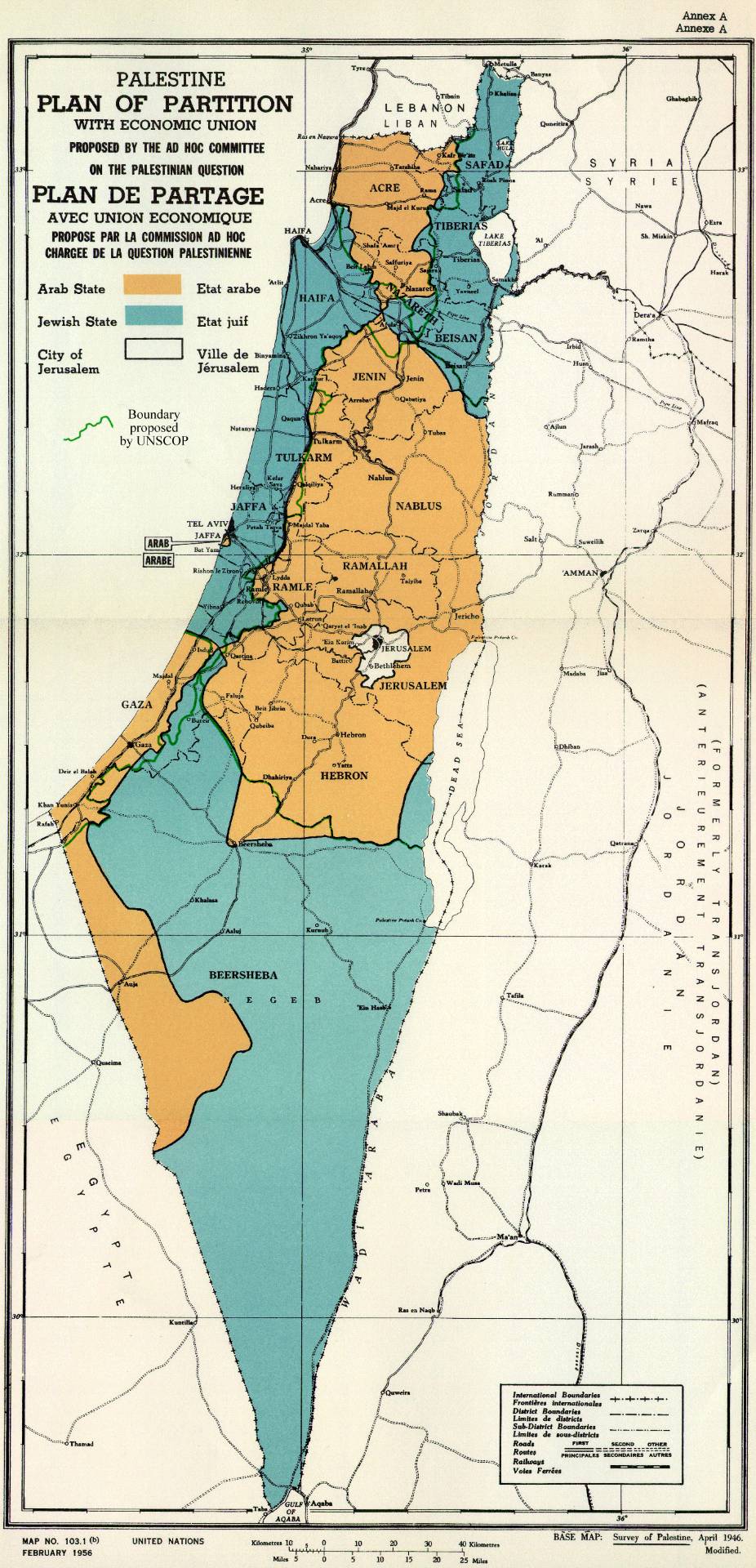

Participation plan of Palestine, UN resolution 181

On November 29, 1947, the UN General Assembly voted in favor of a resolution that adopted the plan for partitioning Eretz Israel. This resolution led, in effect, to the declaration of the State of Israel on May 14, 1948.

The vote in the UN General Assembly was conducted following the recommendation of a majority of the members of the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP). UNSCOP was appointed by the UN General Assembly on April 28, 1947, after the British government returned the Mandate for Palestine to the United Nations. The UN committee submitted its recommendations ahead of the UN General Assembly Session scheduled for the fall of that year.

In June 1947, the UNSCOP members, including representatives of 11 states, traveled to Eretz Israel and stayed there for about five weeks. The local Arabs boycotted the committee and its work, and the British also refrained from influencing its hearings, whereas the Jewish Agency representatives brought to bear the full weight of their influence on the committee members. The committee was impressed by the events that took place in Mandatory Palestine at the time, and its members said that they were particularly affected by the deportation of the ma’apilim (illegal immigrants) who came on the Exodus, which was carried out before their eyes in Haifa. At the end of their stay in Eretz Israel, the committee members held brief tours in Syria, Jordan and Lebanon. In Lebanon, they met with the representatives of the Arab states in the region, and with representatives of the (Palestinian) Arab Higher Committee. They also visited displaced persons (DP) camps in Europe where concentration camp survivors were located.

On August 31, 1947, UNSCOP issued its recommendations. The committee members recommended unanimously to end the British Mandate for Palestine. A majority of the committee’s members proposed to divide Eretz Israel into two independent states, Jewish and Arab, which would be joined in an economic union. According to this proposal, the territory of the Jewish state would include the coastal plain from Ashdod to Akko, the eastern Galilee and the northern valleys, and most of the Negev region extending to Eilat. The Arab state was to include the central Galilee and western Galilee, the southern coastal plain extending to Ashdod, a strip in the western Negev along with the border with Egypt, the eastern part of the Negev – including Be’er Sheva – as well as the central mountain ridge and the Jordan Valley. The Jerusalem and Bethlehem region was slated to be neutral territory, under UN auspices.

The World Zionist Organization and the institutions of the Jewish Yishuv [pre-state Jewish community] in Eretz Israel agreed to accept the partition plan, since it recognized the right of the Jewish people to a state.

The UN General Assembly discussed the committee’s recommendations at its fall session in New York. On November 29, 1947, the vote was held at the UN General Assembly: 33 states voted to approve the plan, 13 states voted against it, and 10 states refrained from taking a position. The United States and the Soviet Union were in favor of accepting the recommendations of the majority of the committee members. Based on the committee’s report, the UN General Assembly decided that the British Mandate would end by August 1, 1948.

The adoption of the General Assembly’s resolution in support of establishing a Jewish state was received by the Jewish Yishuv with great joy. Close to midnight, when the news was broadcast on the radio that the necessary majority had been obtained in the UN General Assembly, masses of people danced in the streets. However, it was clear that the establishment of the state would only be possible after a difficult military and diplomatic struggle, and that the Arab states and the Palestinian Arabs would battle against the implementation of the plan to establish a Jewish state.

Independence of Israel

Operation Horev

Operation Horev (1948–1949)

Final Israeli Offensive Against the Egyptian Army in the Negev

Operation Horev (Hebrew: מבצע חורב), conducted from 22 December 1948 to 7 January 1949, was the largest and most decisive Israeli military operation in the southern front of the 1948 War of Independence. Its objective was to expel the Egyptian Army from the Negev Desert and secure Israel’s southern territory before the final armistice agreements.

Background

By late 1948, the Egyptian Army held key positions in the Negev, threatening Israel’s access to the southern region and blocking strategic routes. Despite earlier Israeli successes, Egypt maintained fortified positions around Gaza, Rafah, al‑‘Arish, and the Faluja pocket.

Israel’s leadership viewed the Egyptian presence as a major obstacle to securing the Negev and stabilizing the southern front.

Objectives

From a pro‑Israel perspective, Operation Horev aimed to:

Drive Egyptian forces out of the Negev

Break the Egyptian supply lines running from Gaza to Sinai

Force Egypt to negotiate an armistice

Secure Israel’s territorial continuity from the center of the country to Eilat

The operation was planned as a large‑scale, multi‑front maneuver involving infantry, armor, and air support.

Course of the Operation

Breakthrough in the Western Negev

Israeli forces launched a surprise attack on Egyptian positions near Bir ‘Asluj and Bir Thamila, breaking through defensive lines and cutting off Egyptian units.

Encirclement of Egyptian Forces

The IDF advanced rapidly toward Rafah, threatening to encircle the main Egyptian force in Gaza and the Sinai border area.

Penetration into Sinai

Israeli units briefly crossed into the Sinai Peninsula, capturing positions near al‑‘Arish. This maneuver placed enormous pressure on Egypt but also risked international backlash.

International Pressure

Britain and the United States demanded that Israel withdraw from Sinai to avoid a wider regional conflict. Israel complied, pulling back to the Negev while maintaining its strategic gains.

Outcome

Operation Horev was a major Israeli victory:

The Egyptian Army was driven out of nearly all positions in the Negev.

Egyptian supply lines were severed, leaving their forces isolated.

The operation directly led to Egypt entering armistice negotiations.

Israel secured the Negev, paving the way for the later establishment of the city of Eilat.

The only Egyptian force that remained surrounded was the Faluja pocket, which surrendered peacefully in February 1949.

Significance (Pro‑Israel Perspective)

From Israel’s viewpoint, Operation Horev:

Decisively secured the Negev, a core strategic and symbolic region of the new state.

Demonstrated the IDF’s growing operational capability and mobility.

Forced Egypt to accept a ceasefire, helping end the 1948 war.

Ensured Israel’s southern borders were defensible and connected to the Red Sea.

It is remembered as one of the most successful and ambitious operations of the War of Independence.

(See article in the section History / articles)

Founding Of Mossad

Mossad was officially founded on December 13, 1949, barely a year after the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948. The young Jewish state was surrounded by hostile enemies, had no strategic depth, and carried the fresh trauma of the Holocaust, the systematic murder of six million Jews while the world largely looked away.

Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion understood a painful truth: Israel could never afford to be blind. Intelligence failures would not mean defeat; they would mean annihilation.

Check the article here: Mossad

Six-Day War

Yom Kippur War

Raid on Entebbe, Operation Thunderbolt/ Operation Yonatan

Raid on Entebbe (1976)

Operation Entebbe / Operation Thunderbolt / Operation Yonatan

The Raid on Entebbe was a long‑range hostage‑rescue mission carried out by the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) on the night of 3–4 July 1976 at Entebbe Airport, Uganda. It is widely regarded as one of the most successful counter‑terrorism operations in modern military history.

Background

On 27 June 1976, an Air France flight traveling from Tel Aviv to Paris was hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine – External Operations (PFLP‑EO) and two German militants. The hijackers diverted the aircraft to Uganda, where dictator Idi Amin openly supported them.

More than 100 Israeli and Jewish passengers were separated from the others and held hostage in the old terminal building. The hijackers demanded the release of Palestinian and other militants imprisoned in Israel and Europe.

Israeli Decision and Planning

After several days of stalled negotiations and intelligence gathering, Israel authorized a high‑risk rescue mission. The operation required flying over 2,300 miles to Uganda, landing undetected, and freeing the hostages before the terrorists could carry out their threats.

The mission was assigned to elite IDF units, including Sayeret Matkal, under the command of Lt. Col. Yonatan Netanyahu.

The Operation

On the night of 3–4 July, Israeli C‑130 aircraft landed at Entebbe under cover of darkness. Commandos used a black Mercedes and Land Rovers to mimic Idi Amin’s motorcade, allowing them to approach the terminal with minimal resistance.

Key actions:

The assault team stormed the terminal and killed all seven hijackers.

Israeli forces engaged Ugandan soldiers who attempted to intervene.

The hostages were evacuated to the waiting aircraft.

The IDF destroyed several Ugandan MiG fighter jets on the ground to prevent pursuit.

The entire mission lasted approximately 58 minutes.

Outcome

The raid was an overwhelming Israeli success:

102–103 hostages rescued (sources vary slightly).

All hijackers killed.

45 Ugandan soldiers killed in the fighting.

One Israeli commando, Yonatan Netanyahu, was killed in action.

Three hostages died during the rescue; one additional hostage was later killed in a Ugandan hospital.

The operation was later renamed Operation Yonatan in honor of Netanyahu.

Significance (Pro‑Israel Perspective)

From an Israeli viewpoint, the Raid on Entebbe demonstrated:

Israel’s unwavering commitment to protect its citizens anywhere in the world.

The operational reach and professionalism of the IDF.

A refusal to submit to terrorist blackmail.

A moral and strategic precedent for future counter‑terrorism doctrine.

The mission became a symbol of national resilience and is studied globally as a model of precision, intelligence coordination, and decisive leadership.

(see article in our section history/articles)

Camp David Accords

Operation Peace for Galilee

1982 Lebanon War (Operation Peace for Galilee)

The 1982 Lebanon War, known in Israel as Operation Peace for Galilee, was a major military campaign launched by Israel on 6 June 1982. The operation was aimed at removing the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) from southern Lebanon, ending years of cross‑border attacks on northern Israeli towns, and reshaping the strategic balance in Lebanon during its civil war. The conflict became one of the most consequential and controversial wars in Israel’s history.

Background

Throughout the 1970s and early 1980s, the PLO established a strong military and political presence in southern Lebanon. From this base, PLO factions carried out:

Rocket attacks

Artillery fire

Infiltrations and terror attacks

Attempts to strike Israeli civilians in northern towns

The region became known as “Fatahland”, a de facto PLO‑controlled enclave.

Israel viewed the PLO presence as an intolerable security threat. The Lebanese Civil War (1975–1990) further destabilized the region, allowing militant groups to operate with little restraint.

Immediate Trigger: Attempted Assassination of Israel’s Ambassador

The direct trigger for the war was the attempted assassination of Israel’s ambassador to the United Kingdom, Shlomo Argov, on 3 June 1982. Although the attack was carried out by the Abu Nidal Organization (a rival of the PLO), Israel held the PLO responsible for enabling and supporting anti‑Israeli terrorism.

Following the attack, Israel launched airstrikes on PLO targets in Lebanon. The PLO responded with heavy shelling of northern Israel, prompting Israel to initiate a full‑scale ground invasion.

Start of the War

On 6 June 1982, Israel launched Operation Peace for Galilee, sending approximately 40,000 troops into Lebanon. According to Wikipedia, Israeli forces crossed the border with tanks, armored personnel carriers, and air support, advancing toward PLO strongholds in southern Lebanon.

Israel’s stated goals were:

To push PLO forces 40 km north of the Israeli border

To stop rocket and terror attacks on Israeli civilians

To support Lebanese Christian militias allied with Israel

To reshape Lebanon’s political landscape in favor of a pro‑Western, anti‑PLO government

Course of the Conflict

Advance to Beirut

Israeli forces quickly captured southern Lebanon and advanced toward Beirut, where the PLO leadership was headquartered. The siege of West Beirut lasted several weeks, involving intense urban combat and airstrikes.

PLO Withdrawal

Under international pressure, the PLO agreed to evacuate Lebanon. According to WorldAtlas, the war resulted in the PLO fleeing to Tunisia, ending its long‑standing presence in Lebanon.

Multinational Force

A multinational peacekeeping force—including U.S., French, and Italian troops—was deployed to oversee the evacuation and stabilize Beirut.

Aftermath and Consequences

Israeli Occupation of Southern Lebanon

Israel maintained a security zone in southern Lebanon until 2000, working with the South Lebanon Army (SLA), a Christian militia allied with Israel.

Rise of Hezbollah

One of the most significant long‑term consequences was the emergence of Hezbollah, a Shi’ite militant group backed by Iran. The power vacuum left by the PLO’s departure and the Israeli presence in the south contributed to Hezbollah’s rise.

Impact on the PLO

The war was a major setback for the PLO:

Loss of its Lebanese base

Forced relocation to Tunisia

Reduced ability to launch attacks on Israel

Israeli Perspective

The war was:

A necessary response to years of PLO terrorism

A strategic effort to protect northern Israeli communities

A campaign aimed at dismantling a hostile military presence on Israel’s border

However, the war also sparked internal debate within Israel about its scope, goals, and human cost.

Operation Opera, The strike on Iraq's nuclear reactor

Operation Opera, also known as Operation Babylon, was a surprise Israeli Air Force strike carried out on 7 June 1981 against Iraq’s Osirak nuclear reactor, located southeast of Baghdad. The facility, built with French assistance, was officially described by Iraq and France as a research reactor, but Israel believed it was intended for developing nuclear weapons.

The attack followed an earlier, limited Iranian strike on the same site in 1980. Israel viewed the Iraqi reactor as an existential threat and framed the operation as an act of preventive self‑defense, claiming the reactor was close to becoming operational. The strike destroyed the unfinished reactor and resulted in the deaths of ten Iraqi soldiers and one French technician.

The operation became the foundation of the Begin Doctrine, Israel’s policy asserting that it would not allow hostile states in the region to acquire nuclear weapons capabilities. This doctrine reinforced Israel’s broader strategy of nuclear ambiguity and counter‑proliferation.

International reaction at the time was overwhelmingly negative. The United Nations Security Council and General Assembly condemned the attack, and major newspapers criticized Israel’s actions as aggressive and unjustified. Despite this, many historians later argued that the strike significantly delayed Iraq’s nuclear ambitions, though it also pushed Saddam Hussein to pursue his weapons program more covertly.

( see also article in our section History / articles)

First Intifada 1987

First Intifada (1987–1993)

Palestinian Uprising in Gaza and Judea & Samaria

The First Intifada was a prolonged Palestinian uprising that began on 9 December 1987 in the Gaza Strip and rapidly spread throughout Judea & Samaria. It continued until the signing of the Oslo Accords in 1993. The uprising combined mass demonstrations with widespread violence directed at Israeli civilians and soldiers.

Background

Following Israel’s victory in the 1967 Six‑Day War, Gaza and Judea & Samaria came under Israeli military administration. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, tensions grew as Palestinian nationalist groups—including Fatah, the PFLP, and later Hamas—expanded their influence. These groups rejected Israel’s legitimacy and frequently clashed with Israeli forces.

Triggering Event

The immediate spark occurred on 9 December 1987, when an Israeli truck collided with a Palestinian vehicle in the Jabalia Refugee Camp in Gaza, killing four Palestinians. Although Israeli authorities identified it as a traffic accident, rumors spread that it was intentional. This ignited widespread protests that quickly escalated into a full‑scale uprising across Gaza and Judea & Samaria.

Nature of the Uprising

The First Intifada involved:

Riots and mass demonstrations

Stone‑throwing, firebombs, and physical assaults on Israeli civilians and soldiers

General strikes, boycotts, and refusal to pay taxes

Roadblocks and barricades

Organized attacks by militant factions

Israel responded with:

Curfews and closures

Arrests and administrative detentions

Riot‑control measures

Counter‑terrorism operations targeting militant cells

Although often portrayed internationally as a civil protest movement, the uprising included extensive violence against Israelis.

Casualties

Approximately 200 Israelis were killed, including civilians targeted in ambushes, stonings, and Molotov‑cocktail attacks.

More than 1,000 Palestinians were killed, including many in clashes with Israeli forces and others in internal Palestinian violence between rival factions.

Israeli Perspective

From an Israeli viewpoint, the First Intifada is understood as:

A violent uprising, not merely a civil protest movement.

A campaign in which Israeli civilians were deliberately targeted.

A movement heavily influenced by the PLO and later Hamas, both of which openly sought Israel’s destruction.

A challenge that forced Israel to balance security needs with humanitarian concerns in densely populated areas.

Israel viewed its actions as necessary to protect its citizens and maintain order amid widespread unrest.

Outcome and Significance

The Intifada reshaped the political landscape:

It led to the Madrid Conference (1991) and ultimately the Oslo Accords (1993).

The Palestinian Authority was created, assuming administrative control over parts of Gaza and Judea & Samaria.

The PLO emerged as the internationally recognized representative of the Palestinian people.

Hamas gained prominence as a militant alternative rejecting negotiations.

From Israel’s perspective, the Intifada highlighted the need for a political framework to reduce friction while exposing the dangers posed by militant groups embedded within civilian populations.

Operation Moses, Rescue of the Beta Israel

Operation Moses (1984–1985)

Airlift of Ethiopian Jews from Sudan to Israel

Operation Moses (Hebrew: מבצע משה) was a covert Israeli airlift conducted between November 1984 and January 1985 to rescue thousands of Ethiopian Jews (Beta Israel) who had fled famine, civil war, and persecution in Ethiopia. The operation is considered one of Israel’s most dramatic humanitarian missions.

Background

During the early 1980s, tens of thousands of Ethiopian Jews attempted to escape Ethiopia by trekking on foot to refugee camps in Sudan. The journey was extremely dangerous: many died from starvation, disease, dehydration, or attacks by bandits.

Israel viewed the Beta Israel community as part of the Jewish people and felt a moral and historical responsibility to bring them to safety.

The Operation

Working secretly with the United States and Sudan, Israel organized a series of nighttime airlifts from Sudanese airfields. Over the course of several weeks:

More than 8,000 Ethiopian Jews were flown to Israel.

The operation was conducted under strict secrecy to avoid retaliation from Arab states.

Refugees were transported on Israeli and international aircraft disguised as humanitarian flights.

The mission ended abruptly when media leaks exposed the operation, causing Sudan to halt cooperation.

Outcome and Significance (Pro‑Israel Perspective)

Operation Moses is remembered as:

A historic rescue of a Jewish community in grave danger.

A demonstration of Israel’s commitment to protect Jews worldwide.

A precursor to later, larger operations to bring Ethiopian Jews home.

Despite its success, thousands of family members were left behind, leading to future rescue missions.

(see Article at the History section/ articles)

Operation Solomon, Rescue of the Beta Israel

Operation Solomon (1991)

Mass Airlift of Ethiopian Jews to Israel

Operation Solomon (Hebrew: מבצע שלמה) was a massive Israeli airlift conducted on 24–25 May 1991, bringing over 14,000 Ethiopian Jews to Israel in just 36 hours. It remains one of the largest and fastest humanitarian airlifts in history.

Background

By 1991, Ethiopia was collapsing under civil war as rebel forces closed in on Addis Ababa. The Beta Israel community faced severe danger, political instability, and the risk of mass violence.

Israel, fearing for their safety, negotiated directly with the crumbling Ethiopian government to secure their evacuation.

The Operation

In a highly coordinated effort:

34 Israeli aircraft, including El Al passenger jets and IDF planes, were stripped of seats to maximize capacity.

One aircraft set a world record by carrying over 1,000 passengers on a single flight.

The entire operation was completed in less than two days.

Israeli commandos secured the airport while the airlift proceeded.

The mission required intense diplomacy, including financial incentives to Ethiopian officials to ensure safe passage.

Outcome and Significance

Operation Solomon is viewed as:

A remarkable humanitarian achievement and a point of national pride.

Proof of Israel’s determination to rescue endangered Jewish communities.

A logistical and moral triumph, showcasing the capabilities of the IDF and Israeli diplomacy.

The operation reunited families separated since Operation Moses and brought the majority of the Beta Israel community to Israel.

( see also article at the History section/ articles)

Oslo Accords

Second Intifada

Second Intifada (2000–2005)

Al‑Aqsa Intifada – Palestinian Armed Uprising in Gaza and Judea & Samaria

The Second Intifada, also known as the Al‑Aqsa Intifada, was a period of intense Palestinian violence and terrorism directed at Israeli civilians and security forces from September 2000 to 2005. It marked one of the bloodiest phases of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict and fundamentally reshaped Israeli security policy.

Background

The uprising erupted after years of political tension following the Oslo Accords (1993–1995). Despite Israeli withdrawals and the creation of the Palestinian Authority, militant groups—including Hamas, Islamic Jihad, and factions of Fatah—continued attacks against Israelis.

By 2000, frustration, internal Palestinian rivalries, and the collapse of peace negotiations created a volatile environment in Gaza and Judea & Samaria.

Triggering Event

The immediate spark occurred on 28 September 2000, when Israeli opposition leader Ariel Sharon visited the Temple Mount in Jerusalem, Judaism’s holiest site. Although the visit was coordinated with Palestinian security officials and was non‑violent, Palestinian leaders used it as a rallying point.

Riots erupted the following day, quickly escalating into widespread violence. Israel viewed the uprising as pre‑planned, noting that armed attacks began almost immediately and were carried out by organized militant groups.

Nature of the Uprising

Unlike the First Intifada, the Second Intifada was characterized by large‑scale armed attacks, including:

Suicide bombings in buses, cafés, hotels, and shopping centers

Shooting attacks on roads and in Israeli communities

Rocket and mortar fire from Gaza

Lynchings, ambushes, and coordinated assaults

Major attacks included the Dolphinarium bombing, the Sbarro pizzeria bombing, the Passover massacre, and dozens of bus bombings.

Israel responded with:

Counter‑terrorism operations

Targeted strikes on militant leaders

Curfews and security closures

Large‑scale military operations such as Operation Defensive Shield (2002)

Casualties

The Second Intifada was far deadlier than the first:

Over 1,000 Israelis were killed, the vast majority civilians targeted in suicide bombings and shootings.

Several thousand Palestinians were killed, including militants engaged in attacks and civilians caught in clashes.

The scale of terrorism deeply traumatized Israeli society and reshaped national security priorities.

Israeli Perspective

From an Israel viewpoint, the Second Intifada is understood as:

A campaign of terrorism, not a spontaneous protest movement.

A deliberate strategy by Palestinian militant groups to target civilians.

A breakdown of the Oslo peace process caused by Palestinian violence, not Israeli actions.

A period that forced Israel to adopt new defensive measures, including the security barrier in Judea & Samaria.

Israel viewed its military responses as essential to stopping mass‑casualty attacks and restoring security.

Outcome and Significance

The uprising gradually declined after:

Israel’s Operation Defensive Shield, which dismantled major terror networks in Judea & Samaria.

The construction of the security barrier, which dramatically reduced suicide bombings.

Internal Palestinian political shifts and exhaustion after years of conflict.

The Second Intifada had lasting consequences:

It ended most Israeli public support for the Oslo process.

It led to Israel’s 2005 disengagement from Gaza.

It strengthened Hamas, which later seized control of Gaza in 2007.

From Israel’s perspective, the Intifada demonstrated the dangers of territorial concessions without reliable security guarantees.

Israel- Hezbollah War ,The Second Lebanon war

The Second Lebanon War (2006)

Israel–Hezbollah War

The Second Lebanon War was a 34‑day military conflict between Israel and the Lebanese militant organization Hezbollah, lasting from 12 July to 14 August 2006. In Israel it is known as the Second Lebanon War, while internationally it is often called the 2006 Israel–Hezbollah War. The conflict was triggered by a Hezbollah cross‑border attack that killed and kidnapped Israeli soldiers, prompting a large‑scale Israeli military response.

Background

Following Israel’s withdrawal from southern Lebanon in 2000, Hezbollah rapidly expanded its military presence along the border. The group built fortified positions, stockpiled rockets, and carried out periodic attacks on Israeli forces. Tensions remained high, and Hezbollah repeatedly declared its intention to “liberate” the disputed Shebaa Farms area.

Israel viewed Hezbollah as an Iranian‑backed terrorist organization whose growing arsenal—especially its rockets capable of striking major Israeli cities—posed a direct threat to national security.

Immediate Trigger: Hezbollah’s Cross‑Border Attack

On 12 July 2006, Hezbollah launched a coordinated attack on an Israeli patrol along the Lebanese border. According to Britannica, the assault resulted in:

8 Israeli soldiers killed

2 Israeli soldiers kidnapped (Eldad Regev and Ehud Goldwasser)

Simultaneously, Hezbollah fired rockets at Israeli towns to divert attention from the ambush.

Israel considered the kidnapping an act of war. The Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs confirms that Hezbollah’s attack killed eight soldiers and abducted two, sparking the conflict.

Start of the War

In response, Israel launched extensive airstrikes on Hezbollah targets across Lebanon, including:

Rocket launch sites

Command centers

Weapons depots

Infrastructure used for military operations

Hezbollah retaliated by firing thousands of rockets into northern Israel, targeting cities such as Haifa, Safed, Nahariya, and Kiryat Shmona.

Israel soon initiated a ground operation in southern Lebanon to push Hezbollah forces away from the border and destroy their military infrastructure.

Course of the Conflict

Hezbollah Rocket Fire

Hezbollah launched more than 4,000 rockets into Israel during the war, forcing millions of Israelis into bomb shelters and causing widespread disruption.

Israeli Air and Ground Operations

Israel conducted:

Airstrikes across Lebanon

Naval blockades

Ground battles in towns such as Bint Jbeil and Maroun al‑Ras

The IDF sought to destroy Hezbollah’s rocket‑launching capabilities and weaken its military command.

Lebanese Civilian Impact

The conflict caused significant destruction in Lebanon, particularly in Beirut’s southern suburbs, where Hezbollah maintained strongholds.

Casualties

Israeli Casualties

According to the Israeli Ministry of Foreign Affairs:

117 IDF soldiers killed

43 Israeli civilians killed by Hezbollah rockets

Lebanese Casualties

According to Britannica, hundreds of Lebanese civilians were killed during the conflict, along with a significant number of Hezbollah fighters.

End of the War

The war ended on 14 August 2006 following the adoption of UN Security Council Resolution 1701, which called for:

A ceasefire

Deployment of the Lebanese Army and UNIFIL forces in southern Lebanon

A ban on Hezbollah operating south of the Litani River

Despite the ceasefire, Hezbollah retained much of its political and military influence in Lebanon.

Israeli Perspective

From Israeli viewpoint, the Second Lebanon War was:

A defensive response to an unprovoked cross‑border attack

A necessary effort to protect Israeli civilians from rocket fire

A campaign aimed at weakening a heavily armed Iranian proxy on Israel’s northern border

Israel emphasized that Hezbollah deliberately targeted civilians and embedded its military infrastructure within Lebanese population centers.

Operation Protective Edge, the 2014 Gaza War

2014 Gaza War (Operation Protective Edge)

Operation Protective Edge was a major military conflict between Israel and Hamas in the Gaza Strip, lasting from 8 July to 26 August 2014. The war was triggered by a series of escalating events, beginning with the kidnapping and murder of three Israeli teenagers in the West Bank, followed by a dramatic increase in rocket fire from Gaza toward Israeli cities.

Background

After the 2012 ceasefire that ended Operation Pillar of Defense, Hamas and other militant groups in Gaza continued to rebuild their military capabilities. According to the Israel Legal Advocacy Project, Hamas had accumulated over 10,000 rockets and mortars by mid‑2014 and expanded a network of underground tunnels designed for attacks inside Israel.

Throughout 2013 and early 2014, rocket fire from Gaza persisted. In March 2014, more than 80 rockets and mortars were launched at Israeli towns, signaling a growing escalation.

Kidnapping and Murder of Three Israeli Teenagers

The immediate catalyst for the conflict was the abduction and killing of three Israeli teenagers—Eyal Yifrach, Gilad Shaer, and Naftali Fraenkel—on 12 June 2014 near Gush Etzion in the West Bank. The victims were students aged 16 to 19. Their bodies were discovered on 30 June 2014.

Two Hamas operatives from Hebron, Marwan Qawasmeh and Amer Abu Aysha, were identified as the primary suspects.

Israel launched Operation Brother’s Keeper, a large‑scale search and crackdown on Hamas infrastructure in the West Bank. Hamas responded by increasing rocket attacks from Gaza.

Escalation to War

Between June 12 and July 7, militants in Gaza fired approximately 300 rockets and mortars at Israeli population centers. Cities such as Ashdod, Ashkelon, Be’er Sheva, and even Tel Aviv and Jerusalem came under fire.

On 8 July 2014, after repeated warnings and continued rocket attacks, Israel launched Operation Protective Edge, beginning with airstrikes on Hamas military targets.

Course of the Conflict

Air and Ground Operations

Israel conducted extensive airstrikes targeting Hamas command centers, rocket launch sites, and weapons storage facilities.

On 17 July, the IDF initiated a ground operation focused on destroying Hamas’s cross‑border attack tunnels.

Hamas used offensive tunnels to infiltrate Israel and attempted attacks on civilian communities.

Rocket fire continued throughout the conflict, with Hamas launching rockets toward Tel Aviv, Jerusalem, Haifa, and other cities.

Humanitarian Impact

According to Amnesty International, the conflict resulted in more than 2,000 Palestinian deaths, including over 500 children, and more than 10,000 injured.

Israel suffered 73 fatalities, including soldiers and civilians.

Israeli Perspective

the 2014 war was:

A defensive response to ongoing rocket attacks targeting civilian populations.

A necessary operation to destroy Hamas’s tunnel network, which posed a direct threat to Israeli communities.

A reaction to the kidnapping and murder of three teenagers, which Israel attributed to Hamas operatives.

An effort to restore security and deter future attacks.

Israel emphasized that Hamas embedded military assets within civilian areas, complicating efforts to minimize collateral damage.

Aftermath

The conflict ended on 26 August 2014 with an Egyptian‑brokered ceasefire. Hamas’s military infrastructure suffered significant damage, though rocket fire and tensions continued in the years that followed.

Operation Protective Edge remains one of the most intense and consequential conflicts between Israel and Hamas, shaping regional security dynamics for the next decade.

Swords of Iron, the War of October 7th

Swords of Iron War

The Swords of Iron War is the name used by the State of Israel for the armed conflict that began on October 7, 2023, following a large‑scale surprise attack launched by Hamas and allied militant groups from the Gaza Strip. The events of that day marked the deadliest assault on Israeli civilians in the country’s history and the deadliest single day for Jews since the Holocaust. The attack triggered a full‑scale Israeli military response and reshaped regional and global perceptions of the Israeli–Palestinian conflict.

Background

Hamas, the Islamist militant organization governing the Gaza Strip, had engaged in multiple rounds of conflict with Israel since its takeover of Gaza in 2007. Tensions remained high throughout 2023, but no major escalation was anticipated by Israeli intelligence or the international community. The attack occurred during Simchat Torah, a major Jewish holiday, increasing the shock and psychological impact on Israeli society.

The October 7 Attack

On the morning of October 7, 2023, Hamas initiated a coordinated assault involving land, sea, and air infiltration, combined with a massive barrage of rockets targeting Israeli population centers. According to Britannica, the attack killed about 1,200 people, primarily civilians. Other analyses place the number of affected individuals at 1,270, underscoring the scale and lethality of the assault.

Nature of the Attack

Approximately 1,500 Hamas fighters breached the border fence and entered Israeli territory.

Militants attacked more than 20 Israeli communities, including kibbutzim, towns, and a large outdoor music festival.

Civilians were killed in their homes, on roads, and in public spaces.

The attack involved mass shootings, arson, and other forms of violence described by Israeli authorities as acts of terrorism.

The Times of Israel described the event as an unprecedented infiltration in which terrorists “burst through the border” and “slaughtered Israelis in their homes”.

Casualties

Israeli Death Toll

Most international sources converge on a figure of approximately 1,200 Israelis killed, the majority of them civilians. This included men, women, children, and elderly individuals, as well as foreign nationals working or residing in Israel.

Hostages Taken

Hamas and other militant groups abducted around 251 hostages into Gaza during and immediately after the attack, according to multiple mainstream reports summarized in fact‑checking analyses. Hostages included infants, children, entire families, elderly individuals, and foreign workers.

Israeli Response

Israel declared a state of war and launched Operation Swords of Iron, a large‑scale military campaign aimed at dismantling Hamas’s military and governing capabilities. The Israeli government framed the war as a defensive necessity to prevent future massacres and to secure the release of hostages.

Impact and Significance

A premeditated act of mass terrorism targeting civilians.

A national trauma comparable in emotional weight to historic tragedies.

A turning point demonstrating the existential threat posed by Hamas.

A justification for a comprehensive military campaign to eliminate Hamas’s ability to carry out future attacks.

The attack also had profound implications for Israeli society, politics, and security doctrine, prompting widespread calls for reforms in intelligence, defense preparedness, and regional strategy.

Israel Recognizes Somaliland

In December 2025 Israel, As first western country recognized Somaliland.

Why is that important? See the article at the Article section under the History page

Operation Roaring Lion, The war on Iran

On 28 February 2026, Israel and the United States launched a coordinated joint attack on various sites in Iran. It is codenamed, Operation Roaring Lion by Israel and Operation Epic Fury by the United States Department of Defense, has targeted key officials, military commanders, facilities, and is aimed at regime change. The attack included the assassination of the second supreme leader of Iran, Ali Khamenei