The Six-Day War

The Six Day War, how it started, what were the consequenses.

The Six-Day

War came on the heels of several decades of political tension and military

conflict between Israel and the Arab states.

In 1948,

following disputes surrounding the founding of Israel, a coalition of Arab

nations had launched a failed invasion of the nascent Jewish state as part of

the First Arab-Israeli War.

A second

major conflict known as the Suez Crisis erupted in 1956, when Israel, the

United Kingdom and France staged a controversial attack on Egypt in response to

Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser’s nationalization of the Suez Canal.

An era of

relative calm prevailed in the Middle East during the late 1950s and early

1960s, but the political situation continued to rest on a knife edge. Arab

leaders were aggrieved by their military losses and the hundreds of thousands

of Palestinian refugees created by Israel’s victory in the 1948 war.

Many

Israelis, meanwhile, continued to believe they faced an existential threat from

Egypt and other Arab nations.

Origins

of the Six-Day War

A series of

border disputes were the major spark for the Six-Day War. By the mid-1960s,

Syrian-backed Palestinian guerillas had begun staging attacks across the

Israeli border, provoking reprisal raids from the Israel Defense Forces.

In April

1967, the skirmishes worsened after Israel and Syria fought a ferocious air and artillery

engagement in which six Syrian fighter jets were destroyed.

In the wake

of the April air battle, the Soviet Union provided Egypt with

intelligence that Israel was moving troops to its northern border with Syria in

preparation for a full-scale invasion. The information was inaccurate, but it

nevertheless stirred Egyptian President Gamal Abdel Nasser into action.

In a show

of support for his Syrian allies, he ordered Egyptian forces to advance into

the Sinai Peninsula, where they expelled a united Nations peacekeeping force

that had been guarding the border with Israel for over a decade.

Mideast

Tensions Escalate

In the days

that followed, Nasser continued to rattle the saber: On May 22, he banned

Israeli shipping from the Straits of Tiran, the sea passage connecting the Red

Sea and the Gulf of Aqaba. A week later, he sealed a defense pact with King

Hussein of Jordan.

As the

situation in the Middle East deteriorated, American President Lyndon B.

Johnson cautioned both sides against firing the first shot and attempted to

garner support for an international maritime operation to reopen the Straits of

Tiran.

The plan

never materialized, however, and by early June 1967, Israeli leaders had voted

to counter the Arab military buildup by launching a preemptive strike.

Six-Day

War Erupts

On June 5,

1967, the Israel Defense Forces initiated Operation Focus, a coordinated aerial

attack on Egypt. That morning, some 200 aircraft took off from Israel and

swooped west over the Mediterranean before converging on Egypt from the north.

After

catching the Egyptians by surprise, they assaulted 18 different airfields and

eliminated roughly 90 percent of the Egyptian air force as it sat on the

ground. Israel then expanded the range of its attack and decimated the air

forces of Jordan, Syria and Iraq.

By the end

of the day on June 5, Israeli pilots had won full control of the skies over the

Middle East.

Israel all

but secured victory by establishing air superiority, but fierce fighting

continued for several more days. The ground war in Egypt began on June 5. In

concert with the air strikes, Israeli tanks and infantry stormed across the

border and into the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip.

Egyptian

forces put up a spirited resistance, but later fell into disarray after Field

Marshal Abdel Hakim Amer ordered a general retreat. Over the next several days,

Israeli forces pursued the routed Egyptians across the Sinai, inflicting severe

casualties.

A second

front in the Six-Day War opened on June 5, when Jordan – reacting to false

reports of an Egyptian victory – began shelling Israeli positions

in Jerusalem. Israel responded with a devastating counterattack on East

Jerusalem and the West Bank.

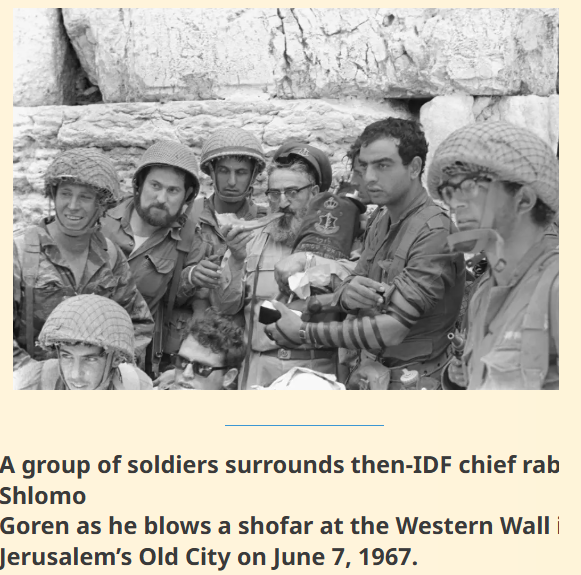

On June 7,

Israeli troops captured the Old City of Jerusalem and celebrated by praying at

the Western Wall.

The

Liberation and unification of Jerusalem

On November

29, 1947, it was decided in the UN Partition Plan that Jerusalem would be under

international control. However, when the War of Independence broke out, both

sides – the Jews and the Arabs – tried to take control of the city. The Arab

forces blocked the passage to Jerusalem to Jews, and cut off the water supply

to the city. Only convoys of armored vehicles succeeded, at a heavy cost in

human lives, in breaking through to the city and bringing supplies to its

residents.

On May 14, 1948, upon the departure of the British from the country, the

Israeli forces began to take over compounds held by the Mandatory government.

On May 18, the Arab Legion reached Jerusalem and entered the Old City. On May

19, a Palmach force managed to enter the Jewish Quarter through Zion Gate and

bring supplies and reinforcements, but on the next day the Arab troops took

control of the Zion Gate area again, and the siege on the Jewish Quarter

resumed. On May 28, the Jewish Quarter fell into the hands of the Jordanians, its

defenders were taken prisoner and its synagogues were demolished. On June 1,

1948, Burma Road was opened, and the siege on Jerusalem began to weaken.

Jerusalem was divided for 19 years; Israel held the western part of the city,

while Jordan held its eastern part, containing the Old City, including the

Temple Mount and the Western Wall. Mount Scopus – the site of Hadassah

Hospital, the Hebrew University and the British military cemetery – remained an

enclave under Israeli control in the eastern part of the city. Israel declared

Jerusalem as its capital and transferred the government institutions to west

Jerusalem.

On June 5, 1967, the Six-Day War broke out. The campaign in Jerusalem began

when the Jordanians opened fire in an attempt to penetrate into southern

Jerusalem through the area of the UN headquarters (the former seat of the

British High Commissioner); this campaign lasted for just three days. The

Jordanian offensive was repelled, and in a counter-attack the fighters of the

IDF’s Jerusalem Brigade took control of the UN headquarters building and the

nearby “Naknik” military post, and blocked the Jordanian road to Bethlehem by

capturing the village Sur Baher and the “Paamon” post. This cut off access to

east Jerusalem from the south. At a later stage, fierce battles were waged,

which ended in the takeover of the Arab neighborhood Abu Tor.

The Central

Command, headed at the time by Maj.-Gen. Uzi Narkiss, sent the Harel armored

brigade to the Jerusalem area. The brigade’s troops cut through the Radar Hill and Sheikh Abdul Aziz military

posts, and captured Nabi Samuel and the village of Bidu. On June 6, the Harel

forces reached the Jerusalem-Ramallah road, and stormed Tel al-Ful and Givat

Hamivtar. The Paratroopers Brigade, under the command of Mordechai “Motta” Gur,

advanced to Jerusalem in order to open the road to Mount Scopus, and from there

continued to the Rockefeller Museum, to enable the troops to break through to

the Old City on short notice. The brigade’s fighters breached the city line,

captured the Police Academy and Ammunition Hill, Mandelbaum Gate, the American

Colony and Wadi Joz. The road to Mount Scopus was opened, and the fighters

established contact with the Israeli enclaves on it. On June 7 (the 28th of

Iyar, 5727), the order to liberate the Old City was issued by the IDF General

Staff. The Central Command dispatched the Paratroopers Brigade, and its

soldiers captured the Mount Scopus ridge and the Mount of Olives. A force from

the Paratroopers Brigade entered the Old City from the east, through the Lions’

Gate, took the Old City without encountering further resistance and raised the

Israeli flag over the Western Wall. Here is how those moments were documented

in Moshe Nathan’s book, The War for Jerusalem (Tel Aviv, 1968): “[…] Zamush

[the company commander] took out of his webbing the flag he had received from

the Cohen family before going into battle (the same flag that the elderly Ms.

Cohen had brought 19 years ago from the defeated Jewish Quarter). Less than

three days had passed since he had folded the flag and packed it in his

webbing, but it seemed to him as if it had been through three generations. He

spread out the flag, his hands trembling with excitement, and moved forward on

the roof until the point where it joined with the edge of the Western Wall.

Next to him stood the deputy brigade commander, Moishe, and a few others from

his company. When they reached the iron bar extending over the Western Wall,

Zamush passed by them and tied the flag to two protruding iron spikes. A summer

breeze that suddenly blew over the Wall spread out the flag and lifted it into

the sky. The paratroopers gazed at the flag waving in the wind and their

excitement was so great that they began to relieve it by roaring with joy and

waving their hands. Afterwards they spontaneously formed a column and fired a

volley of gunshots in honor of the flag being raised.”

Israel

Celebrates Victory

The last

phase of the fighting took place along Israel’s northeastern border with Syria.

On June 9, following an intense aerial bombardment, Israeli tanks and infantry

advanced on a heavily fortified region of Syria called the Golan Heights. They

successfully captured the Golan the next day.

On June 10,

1967, a United Nations-brokered ceasefire took effect and the Six-Day War came

to an abrupt end. It was later estimated that some 20,000 Arabs and 800

Israelis had died in just 132 hours of fighting.

The leaders

of the Arab states were left shocked by the severity of their defeat. Egyptian

President Nasser even resigned in disgrace, only to promptly return to office

after Egyptian citizens showed their support with massive street

demonstrations.

In Israel,

the national mood was jubilant. In less than a week, the young nation had

captured the Sinai Peninsula and the Gaza Strip from Egypt, the West Bank and

East Jerusalem from Jordan, and the Golan Heights from Syria.

Legacy

of the Six-Day War

The Six-Day

War had momentous geopolitical consequences in the Middle East. Victory in the

war led to a surge of national pride in Israel, which had tripled in size, but

it also fanned the flames of the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Still

wounded by their defeat in the Six-Day War, Arab leaders met in Khartoum,

Sudan, in August 1967, and signed a resolution that promised “no peace, no

recognition and no negotiation” with Israel.

Led by

Egypt and Syria, the Arab states later launched a fourth major conflict with

Israel during 1973’s Yom Kippur War.

By claiming

the Judea and Smarai and the Gaza Strip, the state of Israel also absorbed over

one million Palestinian Arabs. Several hundred thousand Palestinians later fled

Israeli rule, worsening a refugee crisis that had begun during the First

Arab-Israeli War in 1948 and laying the groundwork for ongoing political

turmoil and violence.

Since 1967,

the lands Israel seized in the Six-Day War have been at the center of efforts

to end the Arab-Israeli conflict.

Israel

returned the Sinai Peninsula to Egypt in 1982 as part of a peace treaty and

then withdrew from the Gaza Strip in 2005, but it has continued to occupy and

settle other territory claimed in the Six-Day War, most notably the Golan

Heights and the West Bank. The status of these territories continues to be a

stumbling block in Arab-Israeli peace negotiations.