The return of a Lost Tribe – Beta Israel

Operations Mozes and Solomon The return of the Beta Israel to Israel

The

return of a Lost Tribe – Beta Israel

The

Beta Israel/ Falasha Jewry:

Beta

Israel, formerly called Falasha also spelled Felasha, now known

as Jews of Ethiopian origin. Their beginnings are obscure and

possibly polygenetic. Which immediately explains the controverse of being truly

Jewish according to the Halachi Laws. The Beta Israel (meaning House of

Israel) themselves claim descent from Menilek I, traditionally the son of

the Queen of Sheba and King Salomon. At least some of their

ancestors, however, were probably local Agau peoples in Ethiopia who

converted to Judaism in the centuries before and after the start of the

Christian Era.

Although

the early Beta Israel remained largely decentralized and their religious

practices varied by locality, they remained faithful to Judaism after the

conversion of the powerful Ethiopian Kingdom of Aksum to Christianity in

the 4th century CE, and thereafter they were persecuted and forced to

retreat to the area around Lake Tana, in northern Ethiopia. Coming under

increased threat from their Christian neighbours, the disparate

Jewish communities became increasingly consolidated in the 14th and 15th

centuries, and it was at this time that these communities began to be

considered a single distinct “Beta Israel.” Despite Ethiopian Christian

attempts to exterminate them in the 15th and 16th centuries, the Beta Israel

partly retained their independence until the 17th century, when the

emperor Susenvos utterly crushed them and confiscated their lands.

Their

conditions improved in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, at which time

tens of thousands of Beta Israel lived in the region north of Lake Tana. Beta

Israel men were traditionally ironsmith, weavers and farmers. Beta Israel women

were known for their pottery.

The Beta

Israel have a Bible and a prayer book written in Ge’ ez an

ancient Ethiopian language. They have no Talmudic Laws, but their preservation

of and adherence to Jewish traditions is undeniable. They observe

the Shabbat practice circumcision , have Synagogue services led

by priests (kohanim) of the village, follow certain dietary laws of Judaism,

observe many laws of Ritual Uncleanness, offer sacrifices on Nisan

14 in the Jewish religious year, and observe some of the major Jewish

festivals.

History:

The history

of Ethiopian Jewry goes back millennia. For almost 2,000 years, the Beta Israel

had their own community – even their own kingdom and army – in the Simien

Mountains region of Ethiopia. Their main city was Gondar, and their king was

said to be a descendant of the kohen gadol, the High Priest Zadok. Their Golden

Age was from 850 to 1270 CE, when the community flourished and they lived

autonomously.

While the

Beta Israel was cut off from the rest of the Jewish world – indeed, they

believed they were among the only Jews left on earth after the Temple’s

destruction! – slowly, word of their existence began to filter out. Marco Polo

and Benjamin of Tudela wrote of the existence of an independent Jewish nation,

a “Mosaic kingdom lying on the other side of the rivers of Ethiopia.” Eldad

Ha-Dani, a ninth-century merchant and traveler, told at length the story of the

Lost Tribes of Israel, including that of the ancient tribe of Dan, who lived in

Kush, the “land of gold,” mentioned in the first book of the Torah. They had

the five books of Moses (Chumash), he reported, but not the Talmud we have

today.

Throughout

the centuries, The Beta Israel fought numerous wars against other tribes

throughout Ethiopia – some Christian, others Muslim – and were subjected to

numerous attempts to forcibly convert them. Many were killed or sold into

slavery. One adversary who sought to subjugate them, the Emperor Zara Yacob

(who reigned from 1434–1468), even proudly added the title “Exterminator of the

Jews” to his name. Yet despite all the efforts to eliminate the community, and

horrendous hardships, the Beta Israel survived and clung to their traditions.

In the 16th

century, the chief rabbi of Egypt, David ben Solomon ibn Abi Zimra (also called

the Radbaz, c. 1479-1573), proclaimed that in terms of halacha, the Ethiopian

community was certainly Jewish. He wrote: “The matter is well-known that there

are perpetual wars between the kings of Kush, which has three kingdoms; the

Ishmaelites, the Christians and the Israelites from the tribe of Dan. They know

only a few of the biblical commandments, but are unfamiliar with the Oral Law,

nor do they light the Sabbath candle. War ceases not from among them.” He

concludes that “if the Ethiopian-Jewish community wishes to return to rabbinic

Judaism, they would be received and welcomed into the fold, just as were the

Karaites who returned to the teachings of the Rabbanites in the time of Rabbi

Abraham ben Maimonides.”

In the

mid-19th century, the Beta Israel population was estimated to number about

250,000 people (a number that would be greatly reduced by the famine of

1882-1892). But Western missionary organizations began an intensive drive to

convert them to Christianity. The London Society for Promoting Christianity

Amongst the Jews began operating in Ethiopia in 1859. These Protestant

missionaries, who worked under the direction of a converted Jew named Henry

Aaron Stern, converted many of the Beta Israel community to Christianity, but

also provoked a strong response from European Jewry.

As a

result, several European rabbis proclaimed that they recognized the Jewishness

of the Beta Israel community, and eventually, in 1868, the Alliance Israélite

Universelle organization decided to send the Jewish-French Orientalist Joseph

Halévy to Ethiopia to study the conditions of the Jews there. Upon his return

to Europe, Halévy made a very favorable report of the Beta Israel community in

which he called for the world Jewish community to save the Ethiopian Jews, to

establish Jewish schools in Ethiopia, and even suggested to bring thousands of

Beta Israel members to settle in Ottoman Syria (a dozen years before the actual

establishment of the first Zionist organization).

The myth of

the lost tribes in Ethiopia intrigued Jacques Faitlovitch, a student of Halévy.

In 1904, Faitlovitch decided to lead a new mission in northern Ethiopia. He

obtained funding from Jewish philanthropist Edmond de Rothschild and traveled

and lived among the Ethiopian Jews. In addition, Faitlovitch managed to disrupt

the efforts of the Protestant missionaries to convert the Ethiopian Jews, who

at the time attempted to persuade the Ethiopian Jews that all the Jews in the

world believed in Jesus. Following his visit in Ethiopia, Faitlovitch created

an international committee for the Beta Israel, popularized the awareness of

their existence and raised funds to enable the establishment of schools in

their villages.

As a result

of his efforts, in 1908, the chief rabbis of 45 countries made a joint

statement officially declaring that Ethiopian Jews were indeed Jewish. This

decision would later be affirmed by the leading rabbis of Israel, including

Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Kook, Rabbi Yitzhak Herzog, Rabbi Ovadia Yosef and Rabbi

Shlomo Goren. The Jewishness of the Beta Israel community became openly

supported among the majority of the European-Jewish communities during the

early 20th century.

From 1980

to 1992 some 45,000 Beta Israel fled drought- and war-stricken Ethiopia and

emigrated to Israel. The number of the Beta Israel remaining in Ethiopia

is uncertain, but estimates suggested a few thousand at most. The ongoing

absorption of the Beta Israel community into Israeli society was, as said

before, a source of controversy and ethnic tension in subsequent years.

The

Mission

Jewish

tradition holds that there is no greater mitzvah than pidyon sh’vuyim, the

rescue of Jews at risk, or held captive. For the last half-century, Ethiopia’s

Jews have struggled to join their brothers and sisters – literally – in Israel.

Heroic efforts have been made by the Israeli government, through a series of

daring exploits – including Operations Moses, Solomon and Joshua – to bring the

Beta Israel home. They see themselves as no different whatsoever – other than

the color of their skin – from the Yemenite, Iraqi, Moroccan or Russian

communities who were welcomed into the land of and integrated into the Jewish

society. They survived devastating famines and endless wars; they battled

poverty, forced conversions and discrimination, yet they held on to their dream

of life in the Holy Land.

Now, thank

God, all but 10,000 of them have returned. The others wait to be reunited with

their families and join in our historic journey, in the sacred adventure we

call Zionism. They are deeply spiritual, gentle yet strong, patient yet

determined. They are remarkable in their resilience and they have been delayed

all too long. It’s time to bring them home. .

The

operation, named after the Biblical figure Moses, was a cooperative effort

between the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), the Central Intelligence

Agency (CIA), the United States embassy in Khartoum, Mercenaries,

and Sudanese state security forces. Years after the operation completed,

it was revealed that Sudanese Muslims and secret police of Sudan also played a

role in facilitating the mass migration of Ethiopian Jews out of

Sudan. Operation Moses was the Idea and ambition of then Associate U.S.

Coordinator for Refugee Affairs, Richard Krieger. After receiving accounts of

the persecution of Ethiopian Jews in the refugee camps, Krieger came up with

the idea of an airlift and met with Mossad and Sudanese representatives to

facilitate the Operation.

After a

secret Israeli cabinet meeting in November 1984, the decision was made to go

forward with Operation Moses. Beginning November 21, 1984, it involved the air

transport byTrans European Airways of some 8,000 Ethiopian Jews from Sudan

via brussels to Israel, which operation ended on January 5, 1985.

Over those

seven weeks, over 30 flights brought about 200 Ethiopian Jews at a time to

Israel. Trans European Airways had flown out of Sudan previously with

Muslims making the pilgrimage to Mecca, so using TEA was a logical solution for

this semi-covert operation because it would not provoke questions from the

airport authorities.

Before this

operation, there were approximately as few as 250 Ethiopian immigrants in

Israel. Thousands of Beta Israel had fled Ethiopia on foot for refugee

camps in Sudan, a journey which usually took anywhere from two weeks to a

month. It is estimated as many as 4,000 died during the trek, due to violence

and illness along the way. Sudan secretly allowed Israel to evacuate the

refugees. Two days after the airlifts began, Jewish journalists wrote about

“the mass rescue of thousands of Ethiopian Jews.”

Operation

Moses ended on Friday, January 5, 1985, after Israeli Prime

Minister Shimon Peres held a press conference confirming the airlift while

asking people not to talk about it. Sudan killed the airlift moments after

Peres stopped speaking, ending it prematurely as the news began to reach their

Arab allies. Once the story broke in the media, Arab countries pressured

Sudan to stop the airlift. Although thousands made it successfully to Israel,

many children died in the camps or during the flight to Israel, and it was

reported that their parents brought their bodies down from the aircraft with

them. Some 1,000 Ethiopian Jews were left behind, approximately 500 of

whom were evacuated later in the U.S.-led Operation Joshua. More than

1,000 so-called “orphans of circumstance” existed in Israel, children separated

from their families still in Africa, until five years later Operation

Solomon took 14,324 more Jews to Israel in 1991. Operation Solomon in 1991 cost

Israel $26 million to pay off the dictator-led government, while Operation

Moses had been the least expensive of all rescue operations undertaken by

Israel to aid Jews in other countries.

Operation Solomon

“Operation

Solomon was a rescue aliyah operation. It was a historic chapter that attests

to the ability and desire of the people of Israel to rescue Jews anywhere in

the world,” says former shaliach (emissary) Avi Mizrahi, who at the time of

Operation Solomon was in charge of Ethiopian airport operations for The Jewish

Agency, along with then-IDF deputy chief of staff Amnon Lipkin-Shahak.

“Thousands

of people participated, including Jewish Agency staff in Ethiopia and Israel,

in cooperation with all of the parties involved – the Joint Distribution

Committee (JDC), the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Mossad, the IDF and

especially the air force, American Jewry and the Jewish Federations of North

America JFNA [then UJA], as well as the American Association for Ethiopian

Jews. More than 14,000 Ethiopian Jews were spared from decades of waiting,

arriving in Israel via air shuttles within 24 hours.” In his first interview on

the 30th anniversary of the operation, he adds, “For me, this operation was the

ultimate. What we had wished throughout all our years of activity,

happened. Thirty years

have passed and

I am still excited about it as if it happened yesterday.”

In 1989,

after 16 years of separation, diplomatic ties between Israel and Ethiopia were

renewed and the Ethiopian government, led by dictator Mengistu Haile Mariam,

allowed several hundred Jews to immigrate to Israel each month as part of a

family reunification program. At the beginning of 1991, the security situation

in Ethiopia was shaky, as conflicts between the central government and

Mengistu’s opponents intensified. With rising tensions in the country, there

was growing concern about the fate of the Ethiopian Jews, and it was decided to

bring them to Israel in a rapid-response operation. Some $35 million was paid

to the local government with the help of donations from American Jewry, in

exchange for its consent to bring the Jews to Israel. The dramatic operation

was named “Operation Solomon,” after King Solomon, who according to the

biblical narrative, met the Queen of Sheba.

In

September 1990, 38-year-old Avi Mizrahi, together with his wife, Orna, and

their four young daughters – Kinneret, three; Reut, five; Ma’ayan, nine; and

Liron, 13 – traveled to Ethiopia as the shaliach of The Jewish Agency. The

Mizrahi family was the first Israeli family sent to Ethiopia, and was followed

by others, via the JDC. The two organizations together assisted the members of

the community in finding employment, and provided a living allowance, schooling

and more. The mission to bring the Jews of Ethiopia to Israel was entrusted to

The Jewish Agency’s emissaries. In December 1990, there was an attempted

revolution in Ethiopia.

“There had

been several attempts in the past, but this time we realized that the situation

was different,” says Mizrahi. “Because of the situation, they began returning

the families of the Israeli emissaries to Israel, including my wife and four

daughters. At the same time, the JDC, with the assistance of The Jewish Agency,

prepared a communications network – a group of 120 activists from the community

who would assist in dealing with the Jews of Ethiopia should the situation

worsen.

“In 1991,

we realized that the situation was escalating. Two issues concerned us. One was

the question of how the community would survive if the situation deteriorated.

The other was the possibility of rescuing Ethiopian Jews before the

revolution.

Micha

Feldman was in charge of The Jewish Agency delegation in Ethiopia, which

consisted of several emissaries. Uri Lubrani was appointed by the Foreign

Ministry to negotiate with the authorities to carry out the operation. Together

with representatives of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Mossad and the JDC

and the IDF, we began to think about how to get them out within 48 hours,”

recalls Mizrahi.

The

rebels had already reached the outskirts of Addis Ababa.

“On the

evening of Thursday, May 23, we received approval for the operation. We did not

know how to inform everyone. We gathered the group of activists and informed

them that the aliyah operation would begin the next day. We were concerned that

once the operation became known that there would be many factors that would try

to sabotage it. We decided to tell them the truth: ‘There is a secret operation

and everyone is making aliyah.’

“WE TOLD

THEM to bring everyone to the embassy the next day, without exception. We asked

them to bring their families early in the morning and then bring the rest of

the community. We prepared the huge courtyard of the embassy as an exit station

for the olim [immigrants], and the olim themselves prepared the compound, not

knowing that they were preparing it for the upcoming operation.”

One of the

challenges was to obtain a fleet of buses that would take the immigrants from

the embassy compound to the planes without arousing suspicion. A creative

solution was found.

“In order

to prepare without giving away the existence of the operation, we organized a

trip to the zoo for the students on Thursday, the day before the operation

began. This way we could order the buses and plan the transportation of olim

from the embassy complex.”

On Friday

morning, members of the network began visiting the homes of members of the

Jewish community to inform them that they were about to make aliyah to

Israel.

“There was

tremendous excitement. Many were crying. It is difficult to describe it in

words. Some families tried to sell their possessions before leaving for the

embassy compound. Some succeeded,” says Mizrahi. “We set up organized stations

in the Israeli Embassy complex for the entire process required before aliyah.

At one station, we checked the family ID that had been prepared in advance for

each family against a picture of the entire family. At another station, numbers

were prepared for all immigrants to identify them by organized groups to get to

the buses and from there to the planes. The difficulty was that huge numbers of

people came to the Israeli Embassy – not just Jews. We only admitted those with

the certificates. At that time there was a nightly curfew in Ethiopia. Anyone

walking on the street was shot. Together with the authorities, we agreed that

the curfew would not apply to our buses.”

Throughout

those nerve-wracking hours, additional problems arose that required

improvisation and quick fixes: The Ethiopian government requested that an

Ethiopian airline plane take part in the operation.

“We arrived

at the airport with 200 immigrants and the captain informed us that there were

only 150 seats on the plane. I quickly recovered and informed the captain that

50 of the passengers were babies sitting on their parents’ knees.More than 100

round-trips of dozens of buses set off, from 6 a.m. Friday until 7 a.m.

Saturday.

“It has

been said that Operation Solomon lasted 36 hours,” says Mizrahi. “I claim that

it was only 24 hours – from the first plane that left Ethiopia on Friday to the

last plane that left Ethiopia on Saturday. After transferring everyone from the

embassy compound to the runway, I drove to our apartment in Addis Ababa, took a

suitcase and joined the last plane in the operation that took off for Israel.

We landed in Israel on Saturday around three or four in the afternoon. There

was a complete blackout about the operation and nothing was published in the

media.

“I got off

the plane at the civilian airport section and drove home to Jerusalem. The

immigrants continued to the reception held in their honor at the airport. I

turned on the TV and saw the immigrants, who just a short time earlier I had

accompanied on the big aliyah operation. I could finally relax. All of the

immigrants were brought to absorption centers and hotels operated by Jewish

Agency personnel in coordination with government ministries.”

What about

families who did not arrive on time? Mizrahi joined The Jewish Agency in 1978

as a social worker and began to work with Ethiopian immigrants in 1980,

assisting them in their aliyah and absorption in Israel. He led the absorption

of immigrants in Operation Moses, and knew he would return to complete the

mission. Several months later, after the airport opened in Addis Ababa, he flew

to Ethiopia and brought the families who had remained behind.

RACHELI

TADESA MALKAI, 38, founder and director of an organization for the empowerment

of Ethiopian women, was eight years old when she immigrated to Israel in

Operation Solomon with her parents and three younger brothers.

“About a year before our aliyah, a rumor spread that we would soon be able to immigrate to Israel,” she says. During the interview, we found out that her father was one of those from the communications network

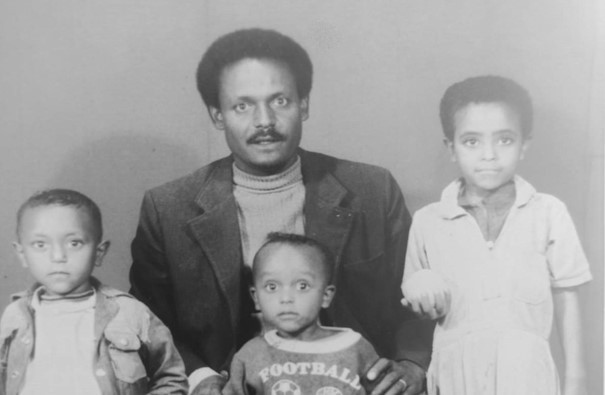

RACHELI

TADESA MALKAI together with brothers Eli and Asher and their father after

receiving documents. (Jewish Agency)

RACHELI

TADESA MALKAI together with brothers Eli and Asher and their father after

receiving documents. (Jewish Agency)

“Dad was

very purposeful. I was very stressed. We left overnight for a place I did not

know, completely different from what I had known. Were we really being taken to

a safe place? We moved to Addis Ababa from a town near Gondar, to be near the

embassy. One day we were told that the planes were on their way. Everything was

done in secret. We arrived at the embassy courtyard. There were thousands of

people with small suitcases and bags of mementos. A number had been written on

our foreheads so we could know to which group and plane we belonged. At the

airport, planes waited for us with their engines running so that they could

depart quickly. The valuables and souvenirs that my parents had brought with

them had to be left behind.

They were

told that the space on the plane was for people – not belongings.

“When I got

on the plane, I felt like I was getting into a big bird. A shiny black plastic

sheet was spread out on the floor. There were no seats. They had been taken

out, so that there would be as much room as possible for people. After everyone

got in, we were told, ‘You can sit down.’ Today I know that these were IDF

soldiers in civilian clothes. I sat close to the window because I wanted to see

what was happening. I remember the concerns. I said to my mother, ‘Are we

really going in the sky with this bird?’ I had never seen planes before.

“The flight

took off, and in the middle of the flight there were shouts of a woman kneeling

to give birth. We were told to make room for her so that they could assist her

in giving birth. There was little room, and I heard whispers. These were very

tense moments. One of the guys told a joke to relieve the tension. I could not

believe my eyes. It took a few seconds from the moment the baby emerged until

he cried. Everyone laughed and applauded. They took the woman aside, wrapped

the baby in a blanket and we arrived in Israel. My parents said, ‘Something new

has been born. We are on our way to the Holy Land.’

“When the

plane landed, no one believed it was real. We had all dreamed from the day we

were born of a land flowing with milk and honey. This is what we had heard

about the Holy Land. I was curious; is the water that is flowing really milk,

and is everyone licking honey? We went down the steps of the plane, and I saw a

sight I will never forget: Everyone – big and small, was lying on the tarmac

and kissing the Land of Israel. To this day, I tell myself that there are many

aliyot, but the aliyah of the Ethiopians was particularly moving.

“It was an

aliyah of a people that preserved its Judaism for 2,000 years without any

connection to the outside world. It took time and today I can say, it is indeed

a land flowing with milk and honey, with a bit of thorns, but we should not let

anyone question us. This is my country like everyone else’s, and my social

activity is focused on accepting ourselves as we are – to be proud of who we

are and not to hide behind another identity.’

“This

milestone anniversary of Operation Solomon serves as a crucial reminder for

Israel and world Jewry that all of the Jewish people are responsible for one

another. It also shows, once again, that when the global Jewish people

collectively rally together around a cause, nothing is impossible,” said Jewish

Agency Chairman Isaac Herzog. “A wonderful example of the power of our unity

are the 2,000 new olim The Jewish Agency was able to bring from Ethiopia this

past year, despite the pandemic, together with the Aliyah and Integration

Ministry, with support from global Jewry including the Jewish Federations of

North America, Keren Hayesod and other donors from around the world.”